Keep the brain in mind

A Peaceable session on neuropsychology, conflict, and learning to work with your nervous system.

You can either watch the webinar or read my article below. Here are my session slides as illustrations for those who prefer to read.

Peaceable exists because our aim is to go beyond conflict. I share tools from a mediator’s toolkit – and that mediator is me. I’ve been a mediator for nearly ten years, and my real passion is to share some of the things I’ve learned along the way, especially the things that have been applicable to me. The hard-won stuff. The things that genuinely changed how I understand conflict, relationships, and my own reactions.

Because here’s the thing: conflict resolution and conflict prevention is work we are all involved in. We’re all invested in it. And it’s lovely to be able to share what I’ve learned — and to learn from other people about how we can have more effective interpersonal communication.

Conflict isn’t “just a disagreement” — it’s a whole-body experience

When we do have interpersonal disagreements, conflict, and difficulties, it can bring up really strong feelings. Not just emotional feelings — physical ones too.

If I asked you, “A friend has said something difficult about you… your manager has something challenging to say… someone’s upset with you…” you might recognise the kind of reactions that often show up:

-

fear

-

anxiety

-

dread

-

confusion

-

heart palpitations

-

tension

That physiological response makes sense.

We are built as tribal beings. Our body wants peace. Our nervous system wants to know we’re not in danger in the group.

And yet conflict happens.

Why do we keep tumbling towards conflict if we hate it?

In mediation work, I’ve seen conflict escalate in ways that shock the people inside it.

Conflict often starts as tension, debate, or avoidance. But if it isn’t interrupted, it can move into alliance and attack, loss of face, threats — and in the worst cases into a red zone of lose-lose conflict where everyone feels harmed, stuck, or deeply resentful.

And I’ve watched people push themselves — sometimes together — right to what feels like the “point of no return.”

Why do we do that?

A big part of the answer is: the brain.

Despite the fact we don’t like conflict, we can tumble towards it because our brain and nervous system are working exactly as designed.

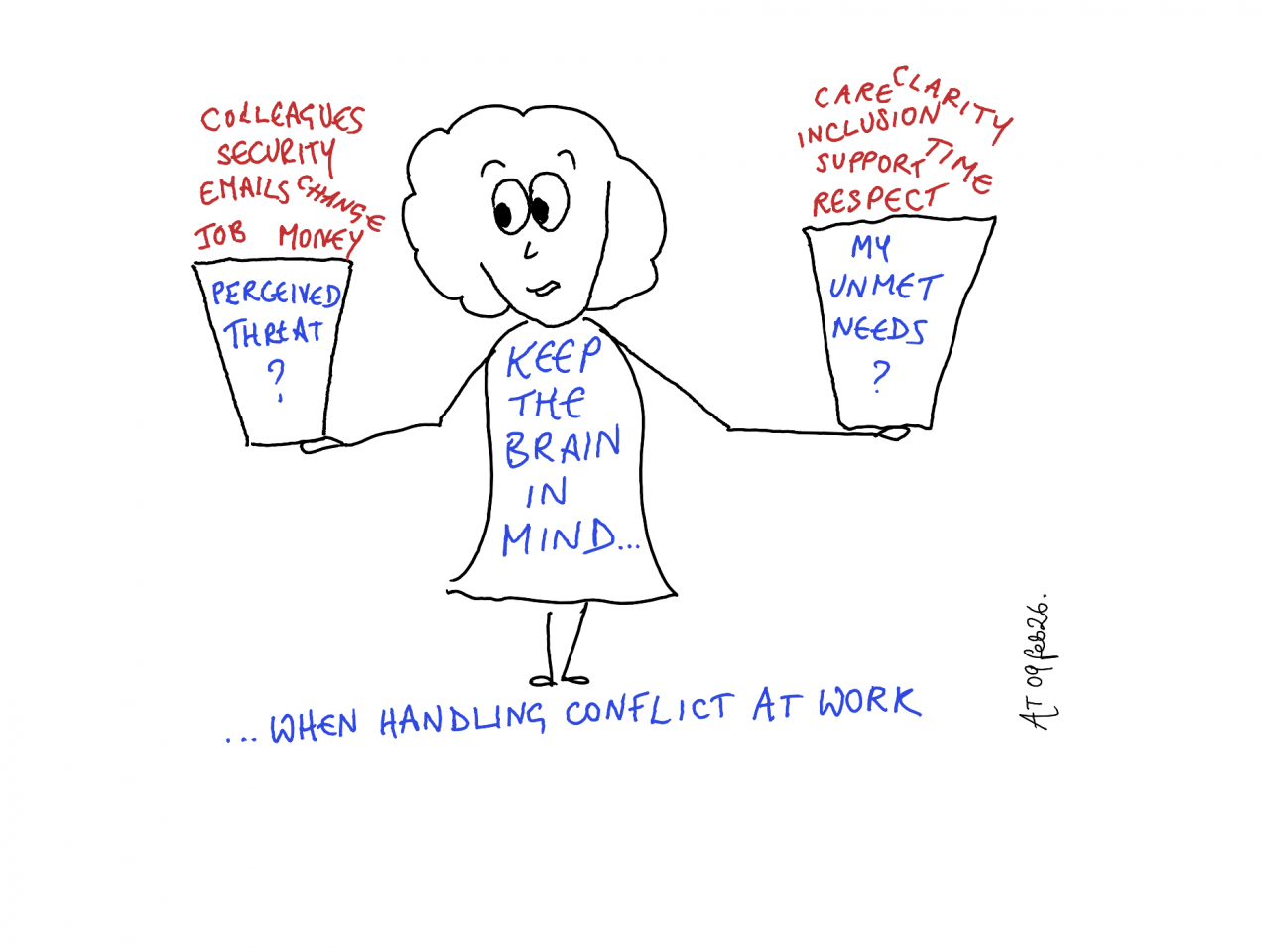

So in this session I offered a simple two-step process for keeping the brain in mind when conflict shows up.

Step 1: Understand what your brain is responding to

When you feel conflict arising — that emotional reaction, that activation, that surge — try asking yourself:

“What is my brain perceiving as a threat here?”

In prehistoric times, the threat might have been a saber-toothed tiger or a mammoth on the horizon. Our brain is brilliantly designed to protect us from immediate danger.

But we’re not facing saber-toothed tigers on a daily basis.

So what does your brain perceive as threat now?

In the session, people shared modern equivalents that the nervous system treats like danger, such as:

-

emails (especially those that feel sharp, overwhelming, or loaded)

-

colleagues who seem frustrated or confused despite having the information

-

deadlines (especially ones you can’t control or escape)

And I love this point: sometimes the “threat” isn’t the task itself — it’s the meaning our brain attaches to it.

The tiger/kitten flip-flop

Neuroleadership author David Rock describes the brain as constantly moving between two states:

-

threat response (tiger)

-

reward response (kitten)

We can feel that flip-flop in real time.

When we’re in a threat response, we’re more alert, more defended, more reactive. When we’re in a reward response, we feel calmer, more open, more connected.

Rock’s SCARF model names five common social triggers that can create either threat or reward:

-

Status – Do I feel respected, valued, seen? Or diminished?

-

Certainty – Do I know what’s happening? Or is it vague and shifting?

-

Autonomy – Do I have choice and agency? Or am I being controlled/micromanaged?

-

Relatedness – Do I feel “with” this person? Or separate and unsafe?

-

Fairness – Does this feel equitable? Or unjust?

These triggers show up everywhere — in the workplace and at home.

Session feedback

Feel it in your body

One of the things I invited people to do in the live session was to notice their body’s response to different statements.

For example:

Status (reward):

“Hey, you handled that meeting really well. Your judgement on the client issue made a big difference.”

Status (threat):

“Yeah, thanks — I’ll take this over. It needs a more senior perspective.”

People often feel the “clench” instantly.

Or:

Certainty (reward):

“The plan is we’ll review options this week, and we’ll make a decision together on Friday.”

Certainty (threat):

“We’ll just see how things go. It might all change depending on what leadership decides.”

Even when someone says “we’ll go with the flow” with good intentions, our nervous system can hear: you’re not safe; you don’t know what’s coming.

And what matters here is this: the person saying the words may have no idea what response they are triggering in you.

SCARF at home too

The same dynamic plays out in relationships.

Autonomy (reward):

“Would you rather talk about this now, or later this evening when things are quieter?”

Autonomy (threat):

“We need to talk about this now, whether you feel ready or not.”

Relatedness (reward):

“I know this is hard for both of us. I’m on your side in this.”

Relatedness (threat):

“You’re just being oversensitive again.”

Our brains are deeply attuned to social cues — and some of us are more sensitive than others, which is one reason people can struggle to understand each other’s reactions.

A quick brain tour: what’s happening when you feel “triggered”

Here’s the short version of the neuropsychology:

When something feels threatening — a look, an email, a tone of voice, even a thought — the signal gets processed through an ancient part of the brain called the limbic system, which includes the amygdala.

The amygdala responds fast. Sometimes so fast that it can react before you consciously register what’s happening.

When it fires, it triggers alert and floods the body with stress chemicals like:

-

adrenaline (to move fast)

-

cortisol (to stay mobilised)

This is hugely useful if a bike is coming at you on the pavement.

But what if the “threat” is something someone has said?

You still get the adrenaline. You still get the cortisol. You still get the surge.

And that can lead to what’s often called amygdala hijack — when your threat system is driving the car.

The 4 F’s: fight, flight, freeze, fawn

In threat response we tend to move into one of four patterns:

-

Fight – “F you.” Anger. Attack. Dominate.

-

Flight – Escape. Avoid. Leave. Shut down the conversation.

-

Freeze – Immobilise. Numb out. Dissociate. Feel unable to act.

-

Fawn – Appease to stay safe. Over-apologise. Don’t say no. Neglect your own needs.

All of these can be trauma-shaped patterns too. They are strategies for safety.

The modern double bind: threat response switches off the part of the brain you actually need

Here’s the painful irony.

While our brains are wired to react to threat, that threat response can reduce our ability to resolve the real problem.

When the amygdala goes off, it essentially sends a message to the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain responsible for rational thinking, decision-making, executive functioning, and social ethics — saying:

We’ve got a crisis. We need all resources for survival. You can take a break — we’re putting you offline for a while.

And that’s a problem, because the prefrontal cortex is exactly what we need for modern conflict: nuance, empathy, self-control, problem-solving, repair, negotiation.

So the work becomes: calm the nervous system so your prefrontal cortex can come back online.

That brings us to step two.

Step 2: Get underneath the conflict iceberg

When you’re in conflict, the visible part is often anger — expressed or suppressed.

But anger is usually the tip of the iceberg.

Anger often shows up to protect us from what’s underneath. If all emotions are messengers, anger often says:

“Watch my boundaries.”

“You’ve overstepped. I’m reasserting them.”

Underneath anger we often find secondary feelings such as:

-

worry

-

hurt

-

frustration

-

sadness

-

offence

-

disappointment

-

feeling diminished

And over time, we can learn to meet our anger with respect — even gratitude — because it’s trying to protect us.

Then, instead of stopping at anger, we ask:

“What are my underlying feelings here?”

“What are my unmet needs here?”

This is often easier to practise outside the most acute moments — as a daily exercise in self-awareness.

“I feel a bit annoyed.”

Okay. That’s my cue.

What’s underneath?

The SCARF + needs “quick diagnostic”

Here’s a quick diagnostic I often return to:

-

Which SCARF domain just took a hit?

Status? Certainty? Autonomy? Relatedness? Fairness? -

What need is calling out underneath this feeling?

Respect? Acknowledgement? Dignity? Appreciation? Connection? Empathy? Belonging? Emotional safety?

When we can name this, we start to create a pathway towards a future conversation — not a demand, but an invitation. Not “you must meet my needs,” but “can we relate in a way that helps me feel safer and more connected?”

This, for me, is part of the journey of advocating for ourselves — especially if your default response (like mine) has often been freeze or fawn.

Five small self-soothing techniques you can use in the moment

This awareness takes time. It’s a practice.

But we can also do small things that help the body hold space for us when we’re activated.

Here are five simple techniques I shared:

-

Lengthen the out-breath

Breathe in for 4, out for 6, three times.

(Practised often, this becomes a powerful “safety” signal to the body.) -

Silently name what’s happening

“I’m noticing activation in myself — and I’m okay.” -

Ground in support

Feet on the floor. Feel the chair holding you. Remember you are in a body, supported. -

Soften one place in the body

Let the jaw drop. Soften the shoulders. Release the brow. Signal to the body: “we’re okay.” -

Choose one micro-choice

“I choose to pause.”

“I choose to take a slow sip.”

“I choose not to reply now, but later.”

These micro-choices can be the difference between escalation and steadiness.

A radical act of self-compassion

We’re walking around in these skin suits, populated by wildly sensitive nervous systems and brains wired for connection.

That’s why connection can feel exquisite — that tingling, calming, ecstatic sense of belonging.

And it’s why disconnection can feel so painful.

Learning to practise self-compassion in the middle of all this is, honestly, a kind of radical act.

And — this is a stretch sometimes — we can even allow the people who trigger us to be part of our learning, because they are showing us where our nervous system needs support, where our feelings are asking to be heard, and where our needs are asking to be named and advocated for.

What if I’m regulated but the other person isn’t?

A wonderful question came up at the end of the session:

What if you’re managing to regulate yourself — but the other person isn’t?

My response was: this is where self-compassion gets its turbocharge.

Because when you recognise your own sensitive, vigilant, caring brain, you can start to see the other person as another human in a skin suit too — with a nervous system that is struggling to regulate.

So you might:

-

give time for their prefrontal cortex to come back online

-

suggest a pause without shaming them (“Shall we come back to this later?”)

-

name the difficulty gently (“This has brought up some hard stuff.”)

-

consider what SCARF domain might have been hit for them

For example, if you’ve given difficult feedback and their status has taken a dent, you might say:

“I hope this feedback doesn’t in any way impact your sense of how much I value what you do.”

And you can almost feel it: ching — status comes back online; the brain can relax.

Are there generational differences in emotional regulation at work?

Another question that followed was about generational differences — and whether people relate differently to emotion and “triggers.”

Yes, I think so.

A lot of what I see in workplace relationships is about different expectations, especially around status and hierarchy.

Many workplaces are moving towards more horizontal ways of relating — and that can be challenging for people who expected a clearer hierarchy, or who came up through a system where authority was expressed very differently.

Workplace etiquette has changed dramatically.

And it takes energy to be around someone with a very different level of self-awareness — which is another reason why keeping the brain in mind is so helpful.

Because it helps you interpret what’s happening as brain behaviour and nervous system behaviour — not just “this person is being difficult.”

A closing invitation

My invitation in this session was awareness.

This is a practice that develops over time. And it’s deeply human.

The more we understand what our brain is doing, the less we need to shame ourselves for our reactions — and the more choice we have in how we respond.

If you’d like to explore this landscape more deeply, I mentioned Brené Brown’s Atlas of the Heart, which maps a wide range of human emotions and experiences, and offers language for the places we go when we’re searching for connection (and what happens when we don’t feel it).

Thank you so much for reading — and for being part of Peaceable. If you’d like reminders for future sessions and access to recordings, you can join my free Peaceable community on Skool.

Keep the brain in mind